Finding 1861–1869 Names of Residents & Civil War Soldiers – Part One,

By William Dollarhide

Most genealogical records created during the decade of the Civil War are related to the soldiers and regiments of the Union and Confederate states. But there are numerous records relating to the entire population of the states as well. This review (in eleven parts) identifies places to look for ancestors during that decade, first for the national name lists, and then a state-by-state listing (in parts two through eleven).

But first, it may be useful to look at the jurisdictions (keepers of records) of the Civil War era, and some history of how these jurisdiction evolved.

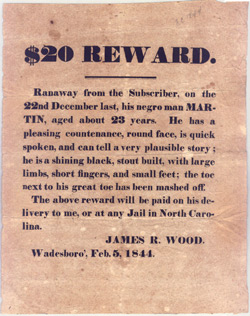

Free vs Slave States: A Line Divides the Nation

A joint survey of the boundary line between the proprietary lands held by William Penn and Charles Calvert was conducted by surveyors Charles Mason  and Jeremiah Dixon in 1763 to 1767. The line remains the current east-west Pennsylvania-Maryland border, and that part of the Maryland-Delaware border which runs approximately north-south. The Mason-Dixon Line became the division between the northern free states and southern slave states.

and Jeremiah Dixon in 1763 to 1767. The line remains the current east-west Pennsylvania-Maryland border, and that part of the Maryland-Delaware border which runs approximately north-south. The Mason-Dixon Line became the division between the northern free states and southern slave states.

The division line was extended in 1787 to the length of the Ohio River upon the creation of the Northwest Territory as part of The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio), the most important legislative act to come out of the Continental Congress prior to the Constitution of the United States of 1789. Specifically, the Northwest Ordinance set up the methods by which new states could be admitted into the Union. First, Congress would have to pass an enabling act which called for a local convention to be convened, a state constitution prepared, and a local vote of approval. This method was used for the creation of virtually all territories, beginning with the Northwest Territory and followed for all subsequent territories. The Northwest Ordinance dictated that the first territory would be a “free” territory – forbidding slavery.

But the Northwest Ordinance did not apply to the original thirteen states, and any new state taken from their original bounds had to have custom enabling acts by Congress, as well as the parent state. For example, the 14th state of Vermont was admitted (as a free state) to the Union in 1791, taken from land claimed and relinquished by both New York and New Hampshire.

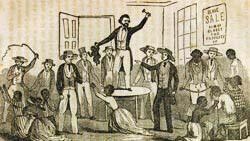

The slavery issue had been a major dividing force in colonial America and for the first seven decades of the United States. Specific religious and ethnic groups in the original thirteen colonies tended to migrate to newly opened lands according to their beliefs relating to the slavery issue. For example, in the early 1800s, North Carolina’s Quakers left for the free states of Ohio and Indiana; while the Scots-Irish headed south to found the slave states of Alabama and Mississippi. New lands opened in the slave states of Kentucky and Tennessee were occupied by both slave and anti-slave proponents, and these “crossroad” states remained intermixed until the time of the Civil War.

From the very beginnings of the United States, the issue of slavery created an intense competition between congressional representatives over the admission of new states. New states were often admitted in twos, one free of slavery, the other permitting slavery. The evolution of slave versus free state at the time of each census year, 1790-1860 shows this balancing act:

From the very beginnings of the United States, the issue of slavery created an intense competition between congressional representatives over the admission of new states. New states were often admitted in twos, one free of slavery, the other permitting slavery. The evolution of slave versus free state at the time of each census year, 1790-1860 shows this balancing act:

1790. By the time of the 1790 census, 94 percent of the 698,000 U.S. slaves lived below the Mason-Dixon Line. But de facto slavery still existed in a few of the northern states. Of the original thirteen states, six were officially ”slave states,” that is, slavery was officially recognized as legal. Vermont joined the Union as a “free state” in 1791, the first state to formally prohibit slavery in its state constitution.

1800. With the addition of the slave states of Kentucky in 1792 and Tennessee in 1796, the U.S. now had eight states north of the Mason-Dixon Line and eight slave states south of the line.

1810. By the time of the 1810 census, the eight states north of the Mason-Dixon Line had all abolished slavery. The admission of the free state of Ohio in 1803 brought the numbers to nine free and eight slave states.

1820. The admission of the three free states of Indiana (1816), Illinois (1818), and Maine (1820), brought the free total to twelve, while the three new slave states of Louisiana (1812), Mississippi (1817), and Alabama (1818), brought the slave state total to eleven.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 allowed Missouri to become a slave state while adding Maine as a free state, and set the limits for further expansion in the West. The northern boundary of Missouri lay almost exactly on the latitude of the Mason-Dixon line of Pennsylvania-Maryland, and the division line from Kentucky at the Mississippi River now moved north up the river to the present Missouri-Iowa line, and then west. By the terms of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the northern Missouri line was supposed to be the new division between any future slave and free states, continuing that line of latitude as far as the western boundary of the United States (the Continental Divide)

1830. With Missouri’s admission as a slave state in 1821, the total went to a balance again with twelve free and twelve slave states.

1840. The admission of the free state of Michigan in 1836, and the slave state of Arkansas in 1837 continued the balance to thirteen slave states and thirteen free states.

1850. In March 1845, Florida was admitted as a slave state. The Republic of Texas, 1836-1845 had permitted slavery, and when Texas was annexed to the U.S. in July 1845, it entered the Union as a slave state. The admission of the free states of Iowa (1846), Wisconsin (1848), and California (1850) brought the totals to sixteen free states and fifteen slave states.

As it turned out, Texas became the last slave state to enter the Union. The fragile agreements between the two factions in Congress fell apart completely when the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed, allowing these two new territories to choose whether they would be slave or free states. This Act had  the effect of revoking the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

the effect of revoking the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

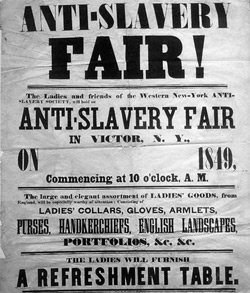

Clearly, the balance of free vs. slave issues in Congress was worsening for the South. After the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, southerners began meeting and discussing the possibility of leaving the Union. The use of the term Confederacy began to appear in print about this time.

1860. With the addition of the free states of Minnesota (1858) and Oregon (1859), the imbalance increased to eighteen free states and fifteen slave states. In addition, the U.S. included five territories destined to become free states: Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington. With an even more imbalance of power in Congress and no hope of seeing any more slave states added to the Union, the break-up of the Union now seemed inevitable.

One other jurisdiction was that of the five civilized tribes of what was unofficially called Indian Territory. Although not a state or a territory, and with no representation in Congress, the Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole Nations all permitted slavery. During the Civil War, the Nations held sympathies for the South.

Southern historians are known for their claim that the Civil War was not fought over the issue of slavery – it was fought over the issue of “States’ Rights.” But northern historians come back with, “Yes, it was fought over the states’ rights to keep slaves.” But, since the precise division line between slave states and free states was not maintained during the Civil War, both northern and southern historians are only partially correct.

Jurisdictions of the Confederate States of America

The departure of southern states from the Union began in December 1860, with South Carolina’s secession; fulfilling their promise to secede if Abraham Lincoln were elected as President. Over the next two months, South Carolina was followed by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. Delegates of these seven states met in Montgomery, Alabama to form the provisional government of the Confederate States of America in February 1861, naming Jefferson Davis as the provisional President.

In April 1861, Virginia joined the Confederacy, followed by Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina in May 1861, for a total of eleven states. The capital of the Confederacy was designated as Richmond, Virginia in May 1861, and the first general election took place on November 6, 1861, in which Jefferson Davis of Mississippi was elected President, and Alexander Hamilton Stephens of Georgia as Vice-President.

The Confederate States accounted for only eleven of the fifteen slaves states as part of the United States before the Civil War. The slave states of Kentucky and Missouri were both officially recognized by the United States of America, and the Confederate States of America, but neither of these swing states formally seceded from the Union. Both had rival Union and Confederate state governments during the war years. The other two slave states were Maryland and Delaware, and both remained with the Union, although the U.S. federal government felt it necessary to impose martial law upon Maryland’s state government to prevent their secession.

The only territory officially added to the Confederate States of America was the Territory of Arizona, an area encompassing the southern half of pre-Civil War New Mexico Territory from Texas to California. From March 1861, the territory was self-proclaimed at a local convention and asserted its desire to join the confederacy. The Confederate Congress recognized the Territory of Arizona in February 1862. But it lasted only until July 1862, when it was occupied by Union forces, and the area returned to the jurisdiction of the U.S. New Mexico Territory.

The five civilized tribes of the Indian Territory were never officially recognized by the Confederacy, but the tribes supplied troops only to Confederate regiments, rather than supporting the Union cause. After the Civil War, the United States revoked their treaties, created new ones, reduced their lands substantially, and began a program to integrate them into U.S. society as “farmers.”

Union States and Expansion, 1861-1864

After the secession of the eleven southern states in early 1861, the Union consisted of the New England states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont; the Mid-Atlantic states of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and the District of Columbia; the Old Northwest states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota; the State of Kansas, admitted in January 1861; and the far west states of California and Oregon, for a total of nineteen states. Of that group, only Maryland supplied soldiers to the Confederate cause, the others were represented by Union troops only.

Kentucky and Missouri were claimed by both the Union and the Confederacy and both had rival state governments for the duration of the Civil War period. About 67% of the troops formed in Kentucky were Union, and 33% Confederate; while the Missouri representation was about 75% Union and 25% Confederate.

Two states were admitted to the Union during the Civil War. First, the anti-slavery counties of Virginia split off as West Virginia in June 1863, joining the Union as its twentieth free state. Then came Nevada, which had been designated a U.S. territory in March 1861, mainly as a means of securing Nevada’s rich gold and silver deposits for the Union. President Lincoln saw statehood for Nevada as a means of obtaining the necessary votes for his upcoming election for a second term. In less than a month, a rush constitution was prepared, telegraphed to Washington, and ratified in October 1864. Nevada increased the total of Union states to twenty-two. Earlier in 1864, Lincoln had pushed through Congress enabling acts for statehood for both Colorado and Nebraska Territories, but these two territories voted against statehood.

During the course of the Civil War, the Union also included the four pre-Civil War territories of Nebraska, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington, all of which supplied only Union troops to the war. New territories established by the Union during the Civil War were Colorado Territory, Feb 1861; Dakota Territory, March 1861; Arizona Territory (U.S.), February 1863; Idaho Territory, March 1863; and Montana Territory, May 1864. Of these five new territories, only Colorado and Arizona supplied troops, although some early soldiers from the others may have been drawn from parent territories of Washington and Dakota. In the case of the U.S. Arizona Territory and its predecessor, the Confederate Territory of Arizona, both supplied troops to the Civil War.

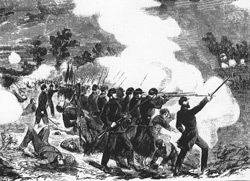

The War Years: April 1861 to April 1865

During the formation period, Dec 1860 – April 1861, southern state forces seized eleven federal forts and arsenals ranging from South Carolina to Texas, all without resistance from Union forces. The first shots of the Civil War were fired at Union-occupied Fort Sumter, South Carolina on April 12, 1861, marking the onset of a conflict that continued until the surrender of the forces by Confederate General Robert E. Lee to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, Virginia on April 8, 1865. The last confederate forces surrendered and Jefferson Davis was captured a month later, essentially ending the Civil War and the Confederate States of America.

During the formation period, Dec 1860 – April 1861, southern state forces seized eleven federal forts and arsenals ranging from South Carolina to Texas, all without resistance from Union forces. The first shots of the Civil War were fired at Union-occupied Fort Sumter, South Carolina on April 12, 1861, marking the onset of a conflict that continued until the surrender of the forces by Confederate General Robert E. Lee to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, Virginia on April 8, 1865. The last confederate forces surrendered and Jefferson Davis was captured a month later, essentially ending the Civil War and the Confederate States of America.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified December 6, 1865, abolished slavery throughout the United States. Ratification of the 13th Amendment was a condition of the return of local rule to those states that had seceded.

Civil War Era Families in the Federal Censuses

Family historians looking for evidence of their ancestors at the beginning of the Civil War decade have at their disposal the names of the inhabitants of the United States from the 1860 Federal Census. This census was taken for every household in America, with a census day of June 1, 1860. As a result, it may be possible to identify every future Union or Confederate soldier and their families about ten months before the Civil War began.

However, a family historian jumping to the 1870 Federal Census to identify the same soldiers or families ten years later faces a difficult task. The reason for this difficulty can be attributed to at least three factors:

First, the 1870 federal census is considered the worst national census ever taken in terms of completeness and accuracy. It is estimated that 5 to 10 percent of the population of the Union states was missed, and 15 to 20% of the former Confederate states was missed. The official population figures of the U.S. increased from about 31.4 million in 1860 to 38.6 million in 1870, thus an additional 7.2 million names were not part of the 1860 census figures. It is estimated that at least half of the increase was due to immigration, rather than a burgeoning birth rate after the Civil War.

Second, from 1861-1865, the Civil War was responsible for at least 620,000 deaths on both sides, a major disruption in the population, and a large statistical bubble over and above the normal mortality attrition rates from the previous decade. In the Confederate states, the number of Civil War deaths were as high as 10% of their total population; and added to the people not counted, as much as 30% of the total people of 1860 who could have been named in the 1870 census, had there been no Civil War.

And third, the devastation and disruption of people and their homes, whether soldiers or civilians, had a major impact on the population and where they lived after the war. Unfortunately, the 1870 federal census identifies a population with little continuity to compare with 1860 names and places.

Follow the Rules

A rule in genealogy is to treat the brothers and sisters of your ancestors as equals. That means that we should spend an equal amount of time and effort finding a brother’s genealogical events, i.e., births, residences, marriages, deaths, etc., as we do for the direct ancestor. By working on close family members, our goal is to find the details about the same set of parents.

This rule is even more important when you learn there was a brother of an ancestor who was a soldier in the Civil War. Your own ancestor may have been too young, or too old, or perhaps wealthy enough to buy himself a substitute to serve in his place. But if a brother were a soldier in the Civil War, there are records available that will aid in identifying an entire family, their places of residence, their migrations, and more. So, even if your direct ancestor did not serve in the Civil War, a close family member may have served, and collecting the wealth of information about that soldier may provide the answers you need.

Start with the Place

All genealogical research requires three things about a genealogical event for every person: 1) The name of the person, 2) an approximate date of the  event, and 3) the place where the event occurred. In most genealogical research tasks, the place of the event needs to be known before you will ever find any records – the place of the event is where a record was created.

event, and 3) the place where the event occurred. In most genealogical research tasks, the place of the event needs to be known before you will ever find any records – the place of the event is where a record was created.

Locating the home of a Civil War soldier is important. The first genealogical event, therefore, may be the day the soldier joined the Army. To be thorough, we need to know his name, date of enlistment, and the place where he enlisted. Since nearly all military regiments were locally raised, finding the regiment a soldier joined ties that person to local town, county, or region of state. This was true for both the Union and Confederate states.

Both forces included a Regular Army, and the Union side had separate troops drawn from Colored Troops, Veteran Reserves, and other non-state Volunteers; but a large majority of all Civil War records listing the names of participants are related to the local regiment in which a soldier served. For example, on the Confederate side, 96% of the soldiers were drawn from state regiments; and on the Union side, nearly 90% of the soldiers were from state regiments.

Knowing the place of enlistment also means that the neighbors of your ancestor can be followed to assist in finding records for both, and used as clues in locating the right person after the war.

So, immediately after you have a name of soldier, the date of enlistment, the place where he enlisted, and the name of the regiment he joined, go back to the 1860 census to find that person in a family. In some cases, a 13-14 year old boy may be shown in the 1860 census who later participated in the Civil War. Thus, the 1860 census may be an aid to understanding the local participants, the place where the regiment was first organized, when they joined, and where they may have landed after the war.

Fortunately, there are now resources available that give the name of a soldier and the regiment to which he was attached.

1861-1869 Censuses & Name Lists

Between the 1860 and 1870 censuses, there are special lists that may help identify people, places of residence, and even family groupings. These 1861-1869 name lists include the actual service records of soldiers, sailors, and marines from both sides of the Civil War, as well as records of pension applications from soldiers on both sides. Both Union and Confederate records of the Civil War era are numerous and mostly extant, providing researchers with the names of virtually all participants on both sides.

The main national military lists are at the National Archives, but a sizeable number of the name lists are still maintained by the states, both Union and former Confederate states. Compiled service records may reveal little about a soldier, other than his name, rank, and regiment. But pension records may reveal names of family members, widows, survivors, etc., for each pension applicant. And, in the several states that offered pensions to their soldiers, there are censuses of the surviving soldiers, some taken well into the 20th century.

Pension records for the Union states are at the National Archives, and an index exists to all applicants for a pension (Available at Ancestry.com). The Confederate pension records are still located at the state in which the pension application was made. Most of these are indexed as well.

Pension records for the Union states are at the National Archives, and an index exists to all applicants for a pension (Available at Ancestry.com). The Confederate pension records are still located at the state in which the pension application was made. Most of these are indexed as well.

Added to the military lists are numerous statewide name lists such as actual state censuses or statewide tax lists. These 1861-1869 name lists of residents need to be identified for anyone hoping to find their ancestors during this difficult period.

Soon after the Civil War, several states conducted statewide censuses, from 1865 to 1869. And, the U.S. federal government levied a national direct tax on individuals to finance the war, taxing that began during the war, but continued for a few years after the war. These and other tax lists for all states survive, and can provide name lists to residents of the U.S. between the 1860 and 1870 federal censuses.

Locating a Civil War Soldier

The starting point for finding Civil War era families is to locate a particular solder, and the regiment(s) he joined. Original records of soldiers from both Union and Confederate states are located at the National Archives. The national lists include the Compiled Service Records for virtually all participants in the Civil War. These records include names of soldiers and sailors from muster lists, prisoner lists, regiment rosters, orders and correspondence, and miscellaneous papers in which a particular soldier was mentioned by name. The records for each soldier were compiled into packets, with a jacket envelope with the name, regiment, and dates of enlistments. The jackets were then indexed, now called the General Index Cards. Both the index cards, jackets and the records within the jackets have been microfilmed. And, recently a project to enter the indexed names and display them online was completed. It is now possible to see the entire Index to Compiled Service Records database online. An index to the soldiers and sailors is online at the National Park Service Website at http://www.civilwar.nps.gov/cwss/.

The Index to Compiled Service Records has been a microfilmed resource for many years, organized by state. The new online index combines all states into one database, and has become the first place to look for a Civil War soldier. Historians have determined that approximately 3.5 million Union and Confederate soldiers actually fought in the War. A soldier serving in more than one regiment, serving under two names, or spelling variations resulted in the fact that there are 6.3 million General Index Cards for 3.5 million soldiers.

Indexed are a total of 6,270,639 names of participants, (4,206,779 Union and 2,063,860 Confederate). You can search for just a surname, or add a first name, whether Union or Confederate, the state of origin (of a regiment, etc.), unit (regiment, company, etc.), or function (infantry, cavalry, etc.)

A breakdown of the numbers of indexed soldiers from each participating state/territory is show in Figure 1.

Forty-four of the modern fifty states are represented. The six states not listed had no Civil War soldiers, or were formed after 1865: Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Oklahoma, and Wyoming.

Note that the numbers of Union troops includes Non-state soldiers drawn from Union Regulars (The permanent U.S. Army, with troops drawn from across the U.S.); Union Veteran Reserves (older regular soldiers with previous service, who were recalled to service during the Civil War); Colored Troops (volunteer soldiers drawn from across the U.S., many of whom were former slaves who had fled to the North from southern states); and an undefined group of Volunteers serving from Non-state units.

The table also shows that virtually every Confederate State supplied at least one brigade/regiment of soldiers to the Union forces; while only the Union state of Maryland supplied a regiment of soldiers to the Confederate Army.

Microfilmed Compiled Service Records

After finding a soldier in the online index, access to the contents of each jacket is now available. The full details with every sheet of paper within each jacket is on microfilm, organized by state then by Civil War regiment. The online index gives you the name, state, and name of regiment, the exact information needed to access the Compiled Service Records. This should be done for every soldier, because there may be more information, more than one regiment, and more than just the names, ranks, dates of service, such as prisoner records, records of promotions, illness, or other facts.

All of the Compiled Service Records were microfilmed by the National Archives as a series for one state, both Union and Confederate states. To locate the Compiled Service Records for Alabama, for example, go to the Family History Library’s Website at www.familysearch.org. From the main page, access “Family History Library,” then “Family History Library Catalog.” Use the place search, and type “Alabama” to get a list of topics available for that state. One topic (about three screen pages into the list) is Alabama – Military Records – Civil War, 1861-1865. Note that there are two Compiled Service Records series, one for the Union and another for the Confederate soldiers. Click on the Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations From the State of Alabama to see the details. Filmed in 1961-1962 by the National Archives, this series has 508 rolls of 16mm film. Going to the “View Film Notes,” it can be seen that there are two name indexes included with the Compiled Service Records, one compiled by the State of Alabama, another from the main Index to Compiled Service Records. The roll contents for the regiments begins with First Cavalry, A-G, 1861-1865, on FHL film #880330. This is how you can access the records for soldiers within a particular regiment. Another complete set of records for Alabama is the Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served in Organizations From the State of Alabama. (10 rolls).

The table shows that Alabama has 197,427 Confederate and 2,842 Union soldier records indexed – this is the place to locate the compiled service record for each.

Repeat these steps for each state in which you want to find the Compiled Service Records. They are all on microfilm, all located at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, and all available on loan to thousands of Branch Libraries around the world.

Civil War Regiments

A source for more information on a Civil War soldier is the many Civil War regimental histories that have been produced over the years. The National Park Service Website has included Union regimental histories from Frederick Dyer’s A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. In progress is a project to include regimental histories for the Confederate units.

At the NPS site, and for each of the Union regiments, there is an alphabetical name list of the soldiers online. After locating a soldier and the name of his regiment, it is now possible to look at all members who ever served for that unit during the Civil War – this is the place where a search for neighbors of your ancestor can be done (assuming you have found names of neighbors from such sources as the 1860 federal census).

From the National Park Service Website, the following description of Civil War Regiments is reproduced: “There are four publications which offer more information on Civil War regiments. Bertram Groene’s Tracing Your Civil War Ancestor discusses several different sources on Civil War regiments. Charles E. Dornbusch’s four volume Military Bibliography of the Civil War contains information on thousands of Civil War publications.

“To discover more information on Union regimental histories one should first look at Frederick Dyer’s A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion which is published by Morningside Press. For Confederate regimental histories, Joseph H. Crute, Jr. and Stewart Sifakis separately compiled Confederate unit histories: Crute’s Units of the Confederate Army which is published by Olde Soldier Books, Inc., 18779 B North Frederick Rd., Gaithersburg, Maryland, 20879; and Sifakis’ A Compendium of the Confederate Armies (11 vols.) which is published by Facts on File, 460 Park Avenue South, New York, New York, 10016.

“As for archives, the National Archives in Washington, D.C. has a wealth of information on Civil War regiments in the Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780s-1917, Record Group 94. The Army’s Military History Institute in Carlisle, Pennsylvania also contains several thousand reference bibliographies on regiments.

“And finally, one may uncover information by visiting or writing to any one of the National Park Service’s battlefield sites. The rangers offer information through talks, walks, films, dioramas, maps, and in many cases they have access to extensive research libraries at the parks.”

Civil War Pension Records

Union States: Records of pensions granted to veterans are often the best military sources because they may give details about the soldier’s residences, spouses, children, widows, survivors, and more. For pensions granted by the U.S. Federal government (Union soldiers only), the records have been gathered together and microfilmed. Two major indexes were compiled which give a soldier’s name, unit, and other details about the pensioner, such as name of spouse/widow, place of residence, survivors, etc. These card indexes have been microfilmed and are available at the Family History Library as follows:

Union States: Records of pensions granted to veterans are often the best military sources because they may give details about the soldier’s residences, spouses, children, widows, survivors, and more. For pensions granted by the U.S. Federal government (Union soldiers only), the records have been gathered together and microfilmed. Two major indexes were compiled which give a soldier’s name, unit, and other details about the pensioner, such as name of spouse/widow, place of residence, survivors, etc. These card indexes have been microfilmed and are available at the Family History Library as follows:

1. General Index to Pension files, 1861-1934, microfilm of original records of the Veterans Administration, Washington, DC, now at the National Archives. Includes index cards for all states, but a reference to pension records for Civil War veterans is limited to Union soldiers, or Union Colored Troops. (Most Confederate pension records are maintained by the former confederate states). Each card gives the soldier’s name, rank, unit, and terms of service; names of relationships of any dependents; the application number; the certificate number; and the state from which the claim was filed. The index cards reproduced on this microfilm publication refer to pension applications of veterans who served in the U.S. Army between 1861 and 1917. The majority of the records pertain to Civil War veterans, but they also include veterans of the Spanish-American War, the Philippine Insurrection, Indian wars, and World War I. Filmed by the National Archives in 1953 as Series T288, 544 rolls of 16mm film, beginning with

FHL film #540757 (Abbott, Clifford – Ackerman, Garrett).

2. Organization Index to Pension Files of Veterans Who Served Between 1861 and 1917, microfilm of original manuscripts for all states at the National Archives, Washington, DC. Filmed by the National Archives, series T0289, 1949, 765 rolls (16mm). The information provided here is virtually the same as that in the General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934, T0288. Unlike the alphabetical General Index, however, this index groups the applicants according to the units in which they served. The cards are arranged alphabetically by state, thereunder by arm of service (infantry, cavalry, artillery), thereunder numerically by regiment, and thereunder alphabetically by veteran’s surname. Use the online index to civil war soldiers to locate a soldier/sailor, which will give the exact unit in which the person served. If the person applied for a pension, this series of records will give additional information about the person. Each card gives the soldier’s name, rank, unit, and terms of service; names of relationships of any dependents; the application number; the certificate number; and the state from which the claim was filed. The index cards reproduced on this microfilm publication refer to pension applications of veterans who served in the U.S. Army between 1861 and 1917. The majority of the records pertain to Civil War veterans, but they also include veterans of the Spanish-American War, the Philippine Insurrection, Indian wars, and World War I. The series begins with FHL film #1725491 (ALABAMA: Unassigned; 1st Alabama Colored Infantry; and Company C, 29th Alabama Infantry).

Confederate States: The U. S. federal government did not provide pensions for Confederate soldiers of the Civil War. Pensions to Confederate participants were granted by each of the eleven former Confederate States, plus the border states of Kentucky, Missouri, and Oklahoma. Since these records are statewide in nature, they are shown under each of the state lists that follow in Parts Two and Three. Detailed information on the Confederate Pension Records and how to access them can be found at the NARA website: www.archives.gov/genealogy/military/civil-war/confederate/pension.html

National Pensioner & Veteran Lists: Union Soldiers

1. List of Pensioners on the Roll January 1, 1883: Giving the Name of Each Pensioner, the Cause for Which Pensioned, the Post-Office Address, and the Date of Original Allowance, 5 vols., 3,952 pages, originally prepared by the United States Pension Bureau, published in 1883 as Senate Executive Document 84, Parts 1-5, reprint by Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., Baltimore, 1970. FHL book 973 M2Lp v. 1-5. This is the official Pension Roll of 1883, the major genealogical source for Civil War and War of 1812 pensioners. Arranged by state or territory, and thereunder by county, it contains the full names of 277,702 persons who were on the Pension Rolls as of 1883, with such information as set forth in the subtitle above. Pensioners residing in the New England states, New Jersey, and the District of Columbia are listed in the first volume; those residing in New York and Pennsylvania in the second; those residing in Iowa, Ohio, and Illinois in the third; and those resident elsewhere (including foreign countries) in the fourth and fifth.

1. List of Pensioners on the Roll January 1, 1883: Giving the Name of Each Pensioner, the Cause for Which Pensioned, the Post-Office Address, and the Date of Original Allowance, 5 vols., 3,952 pages, originally prepared by the United States Pension Bureau, published in 1883 as Senate Executive Document 84, Parts 1-5, reprint by Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., Baltimore, 1970. FHL book 973 M2Lp v. 1-5. This is the official Pension Roll of 1883, the major genealogical source for Civil War and War of 1812 pensioners. Arranged by state or territory, and thereunder by county, it contains the full names of 277,702 persons who were on the Pension Rolls as of 1883, with such information as set forth in the subtitle above. Pensioners residing in the New England states, New Jersey, and the District of Columbia are listed in the first volume; those residing in New York and Pennsylvania in the second; those residing in Iowa, Ohio, and Illinois in the third; and those resident elsewhere (including foreign countries) in the fourth and fifth.

2. See also Federal Pensioners’ Roll of 1883, a CD-ROM publication by Heritage Quest, North Salt Lake, UT, 1998, which includes a searchable name index and the full textual content of all five volumes. The list contains the names of all people receiving federal pensions for military service. In 1883 most of the pensioners were Civil War veterans, but this list includes pensions for service in the Mexican War, the Cherokee Removal of 1836, the War of 1812 and even a few from the Revolutionary War.

3. 1890 Federal Census of Union Veterans. See Schedules Enumerating Union Veterans and Widows of Union Veterans of the Civil War, microfilm of original records at the National Archives, Washington, DC. An Act of March 1, 1889, provided that the Superintendent of the Census in taking the Eleventh Census should “cause to be taken on a special schedule of inquiry, according to such form as he may prescribe, the names, organizations, and length of service of those who had served in the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps of the United States in the war of the rebellion, and who are survivors at the time of said inquiry, and the widows of soldiers, sailors, or marines.” Each schedule calls for the following information: name of the veteran (or if he did not survive, the names of both the widow and her deceased husband); the veteran’s rank, company, regiment or vessel, date of enlistment, date of discharge, and length of service in years, months, and days; post office and address of each person listed; disability incurred by the veteran; and remarks necessary to a complete statement of his term of service. Most of the 1890 population schedules were destroyed as a result of a 1921 fire in the Commerce Building in Washington, DC. Surviving the fire were about half of the special Veteran schedules, which were organized in bound volumes stored in alphabetical order by state. The schedules for the states of Alabama through Kansas and approximately half of those for Kentucky were lost. Surviving schedules beginning with Kentucky through Wyoming were filmed by the National Archives, 1948, as series M0123, 118 rolls. The FHL has a set of the film, beginning with FHL film #338160 (Kentucky: Boone, Bourbon, Bracken, Campbell, Clark, Fayette, Franklin, Gallatin, Grant, Harrison, Jessamine, Kenton, Owen, Pendleton, Scott, and Woodford Counties).

4. See also 1890 Veterans’ Schedules, Selected States, a CD-ROM publication by Genealogy.com, CD131, This CD contains an index of approximately 385,000 war veterans and veterans’ widows who were enumerated on the special veterans’ schedule of the 1890 United States census. Although the 1890 veterans’ schedule was meant only to record information about Union soldiers and their widows, it also lists information about some Confederate soldiers, as well as soldiers who served in other wars, such as the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War. States represented include Alabama, District of Columbia. Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Maine, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, West Virginia, and Wyoming. In addition, there are a few records from the states of California, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Each indexed entry includes the individual’s first and last name, age, sex, microfilm page number, state, county, and locality of residence at the time of the enumeration.

5. Roll of Honor: Civil War Soldiers, a CD-ROM publication by Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., Baltimore; and Family Tree Maker Family Archives,  Broderbund, 1998. This CD contains images of the pages of all 27 volumes of the Roll of Honor as well as The Unpublished Roll of Honor. Recently published by GPC, these books reference the names of over 200,000 Union soldiers who were buried in national cemeteries, soldiers’ lots, and garrison cemeteries. The Roll of Honor is the only official memorial to the Union dead ever published, and in spite of some omissions and discrepancies, it remains the most comprehensive source of information on Civil War fatalities. Originally compiled by the U.S. Quartermaster’s Department, it was published volume by volume as battlefield sites were surveyed, graves exhumed, and bodies identified and reburied. Information given includes the soldier’s name, rank, regiment, company, date of death, and place of burial. For convenience, a name index to all 27 volumes and The Unpublished Roll of Honor is included on the CD.

Broderbund, 1998. This CD contains images of the pages of all 27 volumes of the Roll of Honor as well as The Unpublished Roll of Honor. Recently published by GPC, these books reference the names of over 200,000 Union soldiers who were buried in national cemeteries, soldiers’ lots, and garrison cemeteries. The Roll of Honor is the only official memorial to the Union dead ever published, and in spite of some omissions and discrepancies, it remains the most comprehensive source of information on Civil War fatalities. Originally compiled by the U.S. Quartermaster’s Department, it was published volume by volume as battlefield sites were surveyed, graves exhumed, and bodies identified and reburied. Information given includes the soldier’s name, rank, regiment, company, date of death, and place of burial. For convenience, a name index to all 27 volumes and The Unpublished Roll of Honor is included on the CD.

6. See also, Index to the Roll of Honor, compiled by Martha & William Reamy; with foreword and an index to burial sites by Mark Hughes, published by Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., Baltimore, 1995, 1,164 pages. FHL book 973 M2roh.

7. Online Index to Veteran Burials, Veteran’s Administration. The Nationwide Gravesite Locator is a free Website to locate any U.S. veteran, including many Civil War era veterans. From the VA Website: “Search for burial locations of veterans and their family members in VA National Cemeteries, state veterans cemeteries, various other military and Department of Interior cemeteries, and for veterans buried in private cemeteries when the grave is marked with a government grave marker. The Nationwide Gravesite Locator includes burial records from many sources. These sources provide varied data; some searches may contain less information than others. Information on veterans buried in private cemeteries was collected for the purpose of furnishing government grave markers, and we do not have information available for burials prior to 1997.” Visit the search form page at: http://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/j2ee/servlet/NGL_v1

National Civil War Website

Perhaps the most comprehensive Website for general Civil War information is located at: www.civil-war.net/. There are many links to Civil War websites, accessible databases, regimental histories, photographs, and a wealth of published reports, histories, and personal accounts, all with free access.

This blog was originally printed in Everton’s Genealogical Helper, in the Sept-Oct 2006 issue. It has been updated and hotlinked for GenealogyBlog. Part Two to be printed in an upcoming blog, to be found under the “Civil War” category, and will begin a state-by-state study of sources used to find residents and soldiers during the Civil War and reconstruction era of 1861 to 1869.

What an excellent summary! Thanks.

An excellent article, it is very informative. I have to say I really enjoy your blog. Thank you!

Hello,

Thanks for the wealth of information;

this is a fine site.

Pennsylvania should be in this paragraph in the Union:

—–Union States and Expansion, 1861-1864—–

shouldn’t it?

Best Regards,

–paul sentner

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Go back and look an accurate U.S. map. The northern border of Missouri lies almost exactly at the same latitude as the northern limit of West Virginia’s north panhandle– ~40°,37′ North Lat. And NOT that of the Mason-Dixon Line, which lies at ~39°43′ North Lat.–more than 60 miles to the south of WV’s northern limit (and the lat. of MO’s north border).

Moreover, slavery had existed under the French, British & Virginia Commonwealth in what would became IN & IL, for some 67 years before the Northwest Ordinance. And that ordinance unfortunately did VERY poor job of ending slavery in IN & IL. It took state law, and court rulings to finally stop it in those states, in the 19th Century–decades after the ordinance was passed. Other so-called “Free States” (i.e. NJ, NY, etc.) had similar problems ending this “peculiar institution” within their own borders.

Summative narrations like this one contain valuable info. BUT… sometimes,those facts are presented in such a condensed form that erroneous conclusions can be drawn from them. In short, it must be remembered that the history of slavery in America is quite a bit more complicated than can be truly revealed in summative work like this.

Need history of union Civil War soldier William Jenken drummer athletic band