The following article is by my good friend, Bill Dollarhide, taken from his book, Louisiana Name Lists: Published and Online Censuses & Substitutes, 1679-2001.

Prologue: An earlier GenealogyBlog article was Acadian/Cajun Timeline, 1603-1812 with historical events extracted from both the Maine Name Lists and Louisiana Name Lists books. This historical timeline is related to Louisiana separately, beginning with the early French claims and settlements of the Mississippi Basin; and continuing up to the time of Louisiana’s involvement in the Civil War, as follows:

1673. Mississippi River. French missionaries Jacques Jolliet and Louis Marquette left their base in Ste. Sault Marie, and made their way to the Illinois River, which they descended to become the first Frenchmen to find the Mississippi River. They floated down the Mississippi as far south as the mouth of the Arkansas River before returning to the Great Lakes area.

1682. La Louisiane Française. Following the same route as Jolliet and Marquette, René-Robert Cavelier (Sieur de LaSalle) floated down the Mississippi River, continuing all the way to its mouth at the Gulf of Mexico. He then claimed the entire Mississippi Basin for Louis XIV of France, for whom Louisiana was named. Soon after, the French established La Louisiane Française as a district of New France.

1685-1716. French claims in North America during this period included all of Canada from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, plus the entire Mississippi Basin. French Forts and settlements established in the Mississippi region during this period included Prairie du Chien (1685), Arkansas Post (1686), Kaskaskia (1703), and Fort Rosalie/Natchez (1716).

1713. Queen Anne’s War. At the Peace of Utrecht ending the war, France ceded to Britain its claims to the present Maritime Provinces, including the Peninsular part of French Acadia (which the British renamed Nova Scotia). The remaining French claims in North America were contained within two jurisdictions: Quebéc, which included the St. Lawrence River Valley and Great Lakes region; and La Louisiane Française, which extended down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to the Gulf of Mexico. The dividing line was at the Highlands (Terra Haute) on the Wabash River.

1718. La Nouvelle-Orleans (New Orleans) was founded by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne (Sieur de Bienville). It was named for Philippe II, Duke of Orleans, the Regent of France. That year saw the first of many shiploads of French colonists arriving in Louisiana ports.

1719. Baton Rouge was established by the French as a military post.

1721. Arkansas Post. French and German colonists abandoned Arkansas Post, the largest settlement of all of French Louisiana. As a failed farming community, Arkansas Post was typical of the French efforts to colonize North America south of the Great Lakes. Arkansas Post continued as a fur trading post, but except for a handful of military units, the French presence in the Mississippi Basin now became one of single French fur trappers and traders paddling their canoes on the waterways.

1721. German Coast. A group of German immigrants, who had first settled at Arkansas Post, acquired farm land on the east side of the Mississippi River north of New Orleans. Most of them were formerly of the German-speaking Alsace-Lorraine area of France. They easily adapted themselves to the French culture of Louisiana, and later intermarried with the French Acadians coming into the same area. Their main settlements were at Karlstein, Hoffen, Mariental, and Augsburg, all part of the German Coast. The farms they operated were to become the main source of food for New Orleans for decades.

1722-1739. During this period of La Louisiane Française, a few more settlements and trading posts were established, including Fort du Rocher in 1722; Vincennes in 1732; Ste. Genevieve in 1735; and Fort Assumption in 1739.

1755-1758. Expulsion of the Acadians. When the British first took over the area known as Acadia in 1713, they asked the French Acadians to swear allegiance to Britain or leave. Many of the Acadians left the Peninsula (now Nova Scotia), crossing the Bay of Fundy to areas of Continental Acadia still under control of the French (now New Brunswick and Maine). They had a fairly peaceful coexistence with the British until 1755, when the British completed their conquest of Continental Acadia. The British then began forcibly removing Acadians, at first by deporting them to the Atlantic British colonies, but in 1758, they began transporting Acadians back to their homelands in France. Some of the Acadians left voluntarily, making their way to other areas of North America held by the French. A great number of the Acadians had lost their relationship with mother France after several generations in North America. These were the ones who sought out enclaves of Acadians forming over the next five or six years, moving into areas on both sides of the present border between New Brunswick and Maine; while the largest group eventually found a haven in the Lower Louisiana region.

1763. Treaty of Paris. The French and Indian War in colonial America ended. In Europe and Canada, it was called the Seven Years War. As the biggest loser in the war, France formally ceded all of its North American claims – Louisiana on the western side of the Mississippi was lost to Spain, the eastern side of the Mississippi and all of French Quebéc went to Britain. Soon after the treaty, all French military personnel left their North American posts. But, French civilian settlements continued in Lower Louisiana, such as New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Arkansas Post, and Natchez; and in Upper Louisiana, such as Prairie du Chien, Kaskaskia, and Vincennes. Spain did not take military control of Spanish Louisiana until 1766 (at New Orleans) and 1770 (at St. Louis).

1764-1765. Acadian Coast. In 1764, British forces completed the deportation of French Acadians from their homes in present Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Maine. The remaining Acadians were all herded onto ships. The destinations were not always clear, and the displaced Acadians were sometimes unloaded in Boston, New York, Baltimore, Savannah, Charleston, or Mobile. After a few initial families made their way to New Orleans via Mobile in early 1764, several shiploads of Acadians arrived in New Orleans in early 1765. Their first settlements were on the west side of the Mississippi River, near the present areas of St. James and Ascension Parishes. That first area became known as the Acadian Coast. Today there are 22 parishes of Louisiana considered part of Acadiana, a modern description of the region of southern Louisiana west of the Mississippi River first settled by French Acadians. For more details on the first Acadians in Louisiana, visit the Acadian-Cajun Genealogy & History website.

1766. Antonio de Ulloa became the first Spanish governor of Louisiana, headquartered at New Orleans. He was a brilliant scientist (discoverer of the element Platinum), highly regarded by Spanish Royalty, but rose to his highest level of incompetence as a military leader.

1768. The Louisiana Rebellion of 1768 was an attempt by a combined armed force of Acadians, Creoles and German Coast settlers around New Orleans to stop the handover of French La Louisiane to Spain. The rebels forced Spanish Governor de Ulloa to leave New Orleans and return to Spain, but his replacement Alejandro O’Reilly was able to crush the rebellion. O’Reilly, an Irishman turned Cuban, was responsible for establishing military rule in Spanish Louisiana.

1770 – . Colonial Censuses. Original colonial Spanish censuses and name lists are located at the archives in Seville beginning with 1770, also available on microfilm.

1777-1778. During the Revolutionary War, a number of French-speaking Acadians from Louisiana joined their counterparts from the leftover French settlements of Kaskaskia, Vincennes, and Ste. Sault Marie. They were added to the Virginia Militia force commanded by General George Rogers Clark. General Clark later noted that the fiercely anti-British fighters he gained from the French communities contributed greatly to his monumental victories against the British in the conquest of the Old Northwest.

1783. United States of America. The treaty of Paris of 1783 first recognized the United States as an independent nation, with borders from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River, and from present Maine to Georgia. The treaty also reaffirmed the claims of Britain to present Canada; and Spain’s claim to East Florida, West Florida, New Spain (including Nuevo Mexico & Tejas), and Louisiana west of the Mississippi River.

1800-1802. Louisiana. In Europe, France gained title to Louisiana again after trading the Duchy of Tuscany (now Italy) to Spain. However, Napoleon found that his troops in the Caribbean were under siege and unable to provide much help in establishing a French government in Louisiana. Several months later, when American emissaries showed up in Paris trying to buy New Orleans from him, Napoleon decided to unload the entire tract. – legally described as “the drainage of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers.”

1803. Louisiana Purchase. President Thomas Jefferson urged Congress to vote in favor, and the U.S. purchased the huge area from France, doubling the size of the United States. But, new disputed claims to areas of Lower Louisiana now existed between Spain and the U.S., in particular, the area between the Red River and Sabine River in present Louisiana; and the area of West Florida, east of the Mississippi River.

1804-1805. Orleans Territory and Louisiana District. In 1804, Congress divided the Louisiana Purchase into two jurisdictions. Orleans Territory had north and south bounds the same as the present state of Louisiana, but did not include its present Florida Parishes, and its northwest corner extended on an indefinite line west into Spanish Texas. The first capital of Orleans Territory was New Orleans. For a year, Louisiana District was attached to Indiana Territory for judicial administration, but became Louisiana Territory with its own Governor on July 4, 1805. St. Louis was the first capital of Louisiana Territory.

1806. Neutral Ground. The dispute between the U.S. and Spain over the Louisiana-Texas boundary was informally addressed by the two parties. Spain claimed east to the Red River; the U.S. claimed west to the Sabine River. In 1806, they made a temporary compromise with the so-called Neutral Ground, where neither exercised jurisdiction, creating a haven for fugitives. That lack of jurisdiction inspired the French Pirate, Jean Laffite, to use bayous within the Neutral Ground as a base of operations. The boundary issue was not resolved until the Adams-Onis Treaty, ratified in 1821. (Refer to the 1810 Map of Orleans Territory below).

1806. Orleans Territory Census. In its first legislative session of 1806, Orleans Territory authorized a census for that year. Although statistical returns were transmitted to the federal government, there appears to be no name list associated with the census.

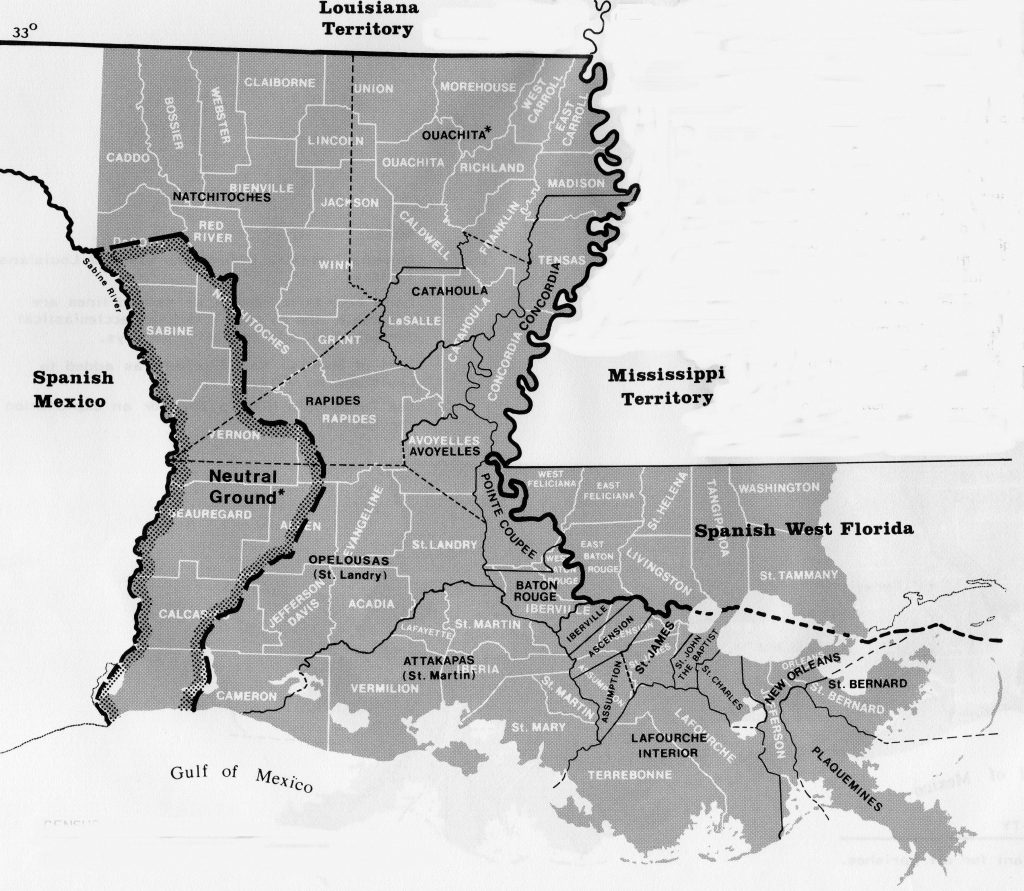

1810. Map of Orleans Territory. The 20 parishes of Orleans Territory at the time of the August 1810 Federal Census are shown in black. The current 64 parishes of Louisiana are shown in white. Parish boundaries shown as dashed lines are uncertain due to poorly defined ecclesiastical jurisdictions and imprecise surveys. The disputed area northwest of the Neutral Ground reflected the view the U.S. held regarding the limits of the Louisiana Purchase. The area of present Louisiana east of the Mississippi is often referred to as “The Florida Parishes.” Map Source: Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses, 1790-1920.

1810-1940. Federal Censuses: The U.S. Federal Census name lists open to the public begin with the 1810 Orleans Territory, followed by Louisiana 1820-1880, and 1900-1940. The LA 1890, like all other states, was lost in a fire in Washington, DC in 1921. A complete 1890 census name list for Ascension Parish, Louisiana is one of only two parishes/counties in the U.S. for which a copy was made and survived in the local courthouse (the other was Washington County, Georgia).

1810. September. A small group of Americans overcame the Spanish garrison at Baton Rouge, and unfurled the new flag of the Republic of West Florida.

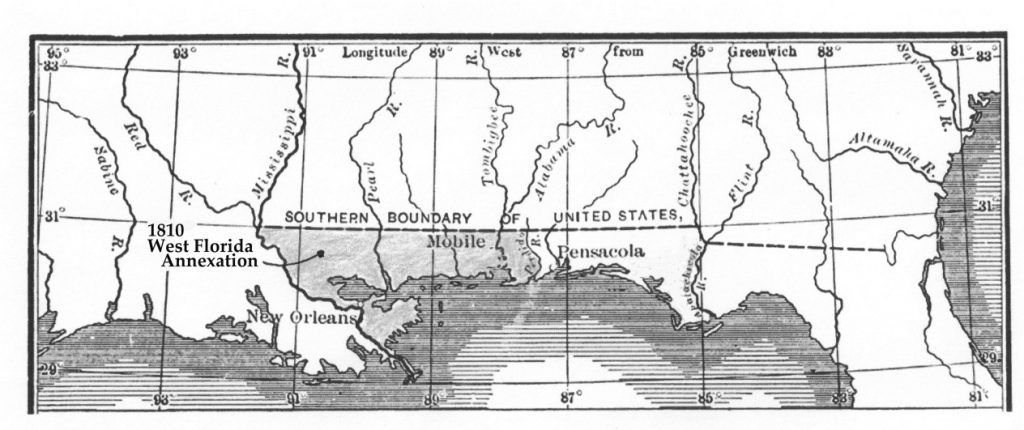

1810 West Florida Annexation

1810. October. In a proclamation by President James Madison, the U.S. arbitrarily annexed Spain’s West Florida from the Mississippi River to the Perdido River, an area that the U.S. believed should have been part of the Louisiana Purchase. The area included the existing towns of Baton Rouge, Biloxi, and Mobile. Spain disagreed that the area was ever part of Louisiana, refused to recognize the annexation, and continued their claim to West Florida in dispute with the U.S. for another ten years.

1811. The side-wheeler steamboat New Orleans was the first Mississippi steamboat. Launched in Pittsburgh, it was first used between Natchez and New Orleans. The port of New Orleans and other ports along the Mississippi River were to see dramatic increases in docking, warehousing, and manufacturing related to the huge increase in river traffic after the introduction of steamboats.

1812. January. Congress added to Mississippi Territory the portion of the West Florida annexation from the Perdido River to the Pearl River, an area which included Mobile and Biloxi; and the portion from the Pearl River to the Mississippi River was added to Orleans Territory, an area that included Baton Rouge.

1812. April 30th. Louisiana Statehood. The same area as old Orleans Territory became the state of Louisiana, the 18th state in the Union. New Orleans was the first state capital.

1812. June 4th. Louisiana Territory was renamed Missouri Territory. For about five weeks in 1812, a Louisiana Territory and a State of Louisiana existed at the same time.

1815. January. Battle of New Orleans. Andrew Jackson commanded an American force of about 3,100 men that prevented an invading British Army with about 7,500 men from seizing New Orleans. Word of the December 1814 Treaty of Ghent officially ending the war had not reached New Orleans yet, and upon the retreat of the British Army, the Battle of New Orleans became the final American victory of the War of 1812. Listen to Johnny Horton – Battle of New Orleans Lyrics for the story.

1821. Adams-Onis Treaty. The treaty included the purchase of Florida, but also set the boundary between the U.S. and New Spain, from Louisiana to the Oregon Country. The treaty established the Sabine River and Red River borders with Spanish Tejas; ending any further claim by the U.S. to Texas as part of the Louisiana Purchase. The treaty also formalized the Arkansas River as the border with Nuevo Mexico; and established Latitude 42° North as the division between California and the Oregon Country. The treaty was named after John Quincy Adams, U.S. Secretary of State, and Luis de Onis, the Spanish Foreign Minister, the parties who signed the treaty at Washington in 1819. It was ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1821. John Quincy Adams was given credit for a brilliant piece of diplomacy by adding the western boundary settlements with Spain to the Florida Purchase.

1833. Louisiana State Census. The constitution of 1812 provided for state censuses to be taken every four years commencing in 1813. It is known that at least some of the years were actually taken, but only the original 1833 state census for St. Tammany Parish has ever been found.

1860. Louisiana Federal Census. Ten months before the start of the Civil War, the June 1860 Federal Census for Louisiana revealed a diverse population of 708,002 people. For example, the African-American slave population of 331,726 was about 47% of the total, the largest percentage of any state. In 1860, the Acadians, German Coast settlers, and Creoles (descendants of colonial French, Spanish, or African settlers) outnumbered the Anglo-Americans, who were less than 20% of the population, the smallest number of any state.

1861-1865. Civil War Era. Louisiana seceded from the Union in January 1861 and joined the Confederate States of America soon after. New Orleans was the largest city in the Confederacy, and was an early target by Union forces to control and maintain the flow of cotton on the Mississippi River to northern textile manufacturers. The city was captured in April 1862 and ruled by a Union Army General for the duration of the war.

Further Reading:

Louisiana Name Lists: Published and Online Censuses & Substitutes, 1679-2001 (Printed Book), softbound, 99 pages, Item FR0245.

Louisiana Name Lists: Published and Online Censuses & Substitutes, 1679-2001 (PDF eBook), 99 pages, Item FR0246.

Acadian/Cajun Timeline, 1603-1812, a GenealogyBlog article.