The following article was written by my good friend, William Dollarhide. Enjoy…

Dollarhide’s Genealogy Rule No. 16: A good genealogical event is learning that your parents were really married.

The discovery and collection of recorded events from a person’s life is the foundation for all genealogical research. It is how we connect people from father to son, and it is how we prove that what we say is true. Before we can put together a family, we need to collect the genealogical events for each member of the family. Before we can extend a pedigree, we need to identify the genealogical events that are used to connect a person to his or her parents.

What are Genealogical Events?

Any written account of a person, however slight, is a genealogical event, and adds valuable knowledge about a person’s life. The significant genealogical events of a person’s life begin with a birth event, followed by a marriage event, and end with a burial event. But in-between these basic vital statistics are a myriad of events in a person’s life. We are talking about recorded events, which includes anything that happened in a person’s life at a certain time and place, and anything that can be recalled from memory or from written accounts. These in-between events include, for example, a baptism, a christening, or an event in which a person was recorded in history for some noteworthy deed, good or bad. The day someone entered school is a genealogical event, as is the graduation day.

Certain documents may contain multiple events for multiple persons. For example, a name of a person mentioned in an obituary as a survivor is a genealogical event, perhaps confirming a date and place where a person lived, as well as a relationship to the deceased. In addition, finding a record such as a land deed showing the residence for a person and the date of the land transaction is a genealogical event.

Name – Date – Place

Each genealogical event should have at least three elements: 1) a name, 2) a date, and 3) a place. For a birth event, we need the person’s full name, the exact date of birth, and the exact place of birth, right down to the city, county, state, or country. As we go back further in time, fewer of the recorded events exist, but even with sparse historical references, it is still possible to find recorded events for people. Clearly, the more events we can identify for a person, the more we learn about them.

Of the three elements for each genealogical event in a person’s life, the most important one is the place. The reason for this is that the location/residence of a person in the past is the same place where you will find a recorded event today. A birth record will be found residing in a state or county where the birth took place. The same is true of marriage records, death records, burial records, obituaries, land records, and virtually every other recorded event in a person’s life. I have a great uncle who was born on a wagon train en route from Iowa to California in 1860. Although the exact location of the birth was never recorded on a birth certificate, a death certificate gave his place of birth as “. . . along the Platte River,” which placed the birth somewhere in present-day Nebraska or Colorado. That genealogical event has a place attached to it, although it is not very precise. Virtually all genealogical events have a place attachment, even if it may be as general as “at sea,” or more narrow, such as, ”USA,” or “Germany,” or very precise, such as “21 Thatcher Street, Boston, Massachusetts.”

Whose Genealogical Events?

As genealogists, we collect historical data about people’s lives, and we sift and organize the data based on categories of relationships. We are interested in three specific categories of human relationships, which are 1) ancestors, 2) collateral people, and 3) suspicious people:

1. Our ancestors are those people directly connected to us through our parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and so on. For each ancestor, we collect all the genealogical events we can find, because this is the group that gets our attention the most.

2. The collaterals are those people indirectly connected to us, e.g., brothers and sisters of our ancestors, along with their offspring. We collect information about these people because understanding their genealogy helps us with our own lines. Since each collateral shares an ancestor with us, they can provide an alternative route of lineage to discover more ancestors.

3. The suspicious are those people we find in our research who have the right name, and lived in the right time and place — which makes them highly suspicious of being an ancestor or at least closely related. Most of us collect facts about these people in great quantities, mainly because we never know if they will turn out to be our ancestors or not.

A Genealogical Event Database

Virtually all of the historical references we find relating to an ancestor, collateral, or suspicious person are individual genealogical events. Sometimes we find events for all three categories of people in the same record we are searching. As we collect these genealogical events, it might be possible to group them all together by making a list of them. And if the issue of relationships is not clear, the list could provide a method of controlling all of the facts about one person, and allowing for judgments to be made about ancestors, collaterals, and suspicious people – all in the same list of events.

As an example from my own family research, I found an 1836 land deed for my ancestor, John Dollarhide, while visiting the Tippecanoe County Courthouse in Lafayette, Indiana. A few pages later in the same book I found another deed for Jesse Dollarhide, John’s younger brother. On a nearby page was an 1832 deed record for a Philip Reynolds, who I suspected to be John Dollarhide’s father-in-law. In the same courthouse, I found a marriage record for John Dollarhide and Lucy Reynolds dated 1836, and another one for Jesse Dollarhide and Nancy Murphey dated 1837. Earlier, I had found an 1850 census entry for Jasper County, Indiana which listed the household of John Dollarhide, age 35, born IN, including Lucy, age 30, born OH, plus several children. An unexpected bonus was finding a Philip Reynolds, age 62, born VA, living with the John Dollarhide household in 1850.

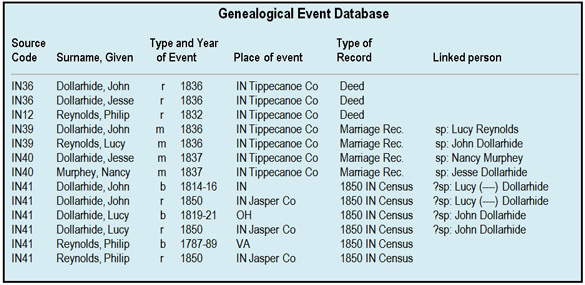

The research for the people mentioned above accounted for thirteen separate genealogical events. I recorded all of the events as single items, including those found for ancestors, collaterals, or suspicious persons. The method I used to record these events was in the form of a Genealogical Event Database (GED). Each of the thirteen events could be identified separately, capturing the names, dates, and places for each. For example, for one event you could write, “Per a land deed dated 1836, John Dollarhide lived in Tippecanoe County, Indiana in 1836,” or, “per an 1850 census listing from Jasper County, Indiana, John Dollarhide was born in Indiana c1815.

Computers Love Databases

For a computer version of the GED, formalizing the elements within each genealogical event became necessary, plus adding a few extra fields. In addition to the name, date, and place of each event, I added a citation of the source document, the type of event, and a name of any person linked to the subject (if that event item had one). In designing my GED database entry for a typical genealogical event, I decided to use the following elements:

GED Elements:

- Source Code (a reference to the document).

- Subject’s Full Name (ancestor, collateral, or suspicious person)

- Type of Event (b=a birth reference, m=marriage, r=residence, d=death)

- Year of Event (exact year or range of years)

- Place of Event (state, county, city, township, etc. where the event occurred)

- Type of Record (census, deed, marriage license, birth record, history, etc.)

- Person Linked to Subject (sp: = spouse, fa: = father, mo: = mother, dau: = daughter, etc.)

Note: (1) A source code refers to a document or page number from my notes and document files. In my system, I use a two-letter code for a state, followed by a page number. So, all the notes and documents are separated by the origin of the records, e.g., a marriage that took place in Indiana may be given the code IN39 to indicate that a copy of the marriage record/document is in the Indiana section, page 39.

Example of a GED Designed for Computers:

The table below shows each of the genealogical events found in my Tippecanoe/Jasper County research, as well as the method I used to organize them. I entered each event into a simple computer database, which became a comprehensive index to all of my documents. Here is an example:

The above GED list is an abbreviated one. A database can contain thousands of entries, representing the names and events of all ancestors you can identify as well as events for collaterals and suspicious people, regardless of surnames or relationship to you. Adding a “Linked Person” as a field is the only possible relationship entry – you can use the GED as way to see possible relationships before you know them for sure. The list is also an indication of genealogical evidence. Using the genealogy rule of “Preponderance of Evidence,” the GED list demonstrates that you have done your homework, have multiple documents, and can prove every statement of relationship you have presented on Family Group Sheets or Pedigree Charts.

Let the Computer do the work

The GED list can now be an index to the Preponderance of Evidence items found in your documents and notes. As a computer file, the power of the GED database is in the ability to organize or reorganize the file in different ways. For example, the entire GED database can be sorted by source code, event, date, place of event, or type of record. An arrangement of the complete list by Surname, Given Name, for instance, will give a list of all genealogical events for one person. A list sorted by Source Code will give the contents of each document, and a list sorted by Place of Event will show what records apply to a particular place. These are functions of any database manager software, but they are also available in most Word Processor software systems.

By entering all genealogical events into this kind of database, a genealogist would have a tremendous index to every person they have found in their research. It doesn’t matter if the person is an ancestor, collateral, or suspicious person. The purpose of the list of names/dates/places is to understand what you have and what you know. But, in addition, the list becomes your documentation list, and a method of citing your sources.

For example, on any family group sheet or family narrative I may prepare for John and Lucy (Reynolds) Dollarhide and family, I can add the list of genealogical events for each member of that family. The same is true for pedigree charts, ancestor tables, or descendancy reports. As it turns out, a GED is an excellent way to cite your genealogical sources, because it can list events separately for each person of interest to a family, pedigree, or descendancy.

What Database?

Excel works, and is easy to use. But, being basically a lazy person when it comes to learning new software, I created my first computer Genealogical Event Database using my word processor. (Yes, word processor!) Word works beautifully. Create a list of items in Word, tab to the next column, and Word interprets the info as a database. You may now sort any column top to bottom, bottom to top, alphabetically, or numerically – just like any database software. And, since all you really need is a list that can be looked at in different ways, the word processor file works quite well. However, custom reports may require the use of a database manager, such as Excel. This is where reports from the database can be unique to a certain place, time period, or surname, such as a report that asks for all persons named Reynolds living in Ohio between 1820 and 1840. One technique is to start small using Word. Then, after the GED file gets larger, a database can be transferred from Word to Excel. Just make sure the new Excel file is set up with at least one line of data, and has columns the same as the Word file. I have gone from Word files to Excel files just using Copy/Paste commands.

Finally, did you ever get mail from a long lost cousin wanting everything you have on their family? I used to send them copies of pedigree charts and family group sheets, sometimes dozens of them. But now, I just send a print-out of my Genealogical Event Database with a note, “This is everything I have on this family – let me know which ones you want copied.”

For Further Reading:

Managing a Genealogical Project

Evidence! Citation & Analysis for the Family Historian

Evidence Explained – Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace

Pingback: Piles of Paper – Part 4 – GenealogyBlog